Key Takeaways

- Discriminatory laws prevented Black families from accumulating generational wealth.

- Personal finance courses can help close racial and gender wealth gaps.

- NEA supports teaching a personal finance curriculum and offers educators resources and tools to help.

As a teenager, Michelle Burton saw both sides of her family live two distinct experiences: One with generational wealth, the other without.

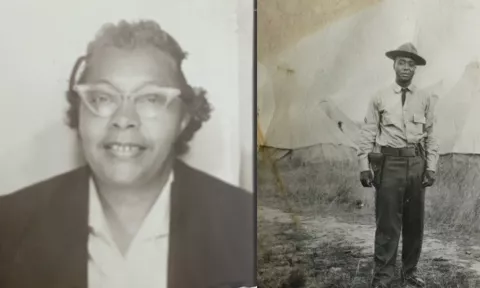

In the late 1800s her paternal great-grandfather owned farmland in rural North Carolina. Some of that land transferred to her grandmother. The land was later used to help Burton's grandfather, a World War II veteran who, after serving, bought a plot of land to build a successful barber shop from the ground up.

“My father inherited some of the land from my grandparents,” shares Burton, a school librarian and president of the Durham Association of Educators.

She adds that when her father moved to Chicago and started his own family, he had the money to buy his own home in 1972.

This is the living definition of generational wealth, financial assets that are passed down through families to children, grandchildren, and beyond.

However, this was not the norm for most Black families. “For example, in 1900, 22 percent of Black families owned homes, compared to 49 percent of white ones. In 2020, 74 percent of white families were homeowners, compared to 45 percent of Black ones,” wrote Jason Lalljee, a junior economic policy reporter for Business Insider.

Housing restrictions and covenant laws

In contrast, Burton’s maternal grandparents lived in Chicago around the mid-1900s. Her grandfather was among the Pullman porters, Black men who assisted passengers aboard trains. To earn higher salaries, better job security, and increase worker protections, the group unionized—making it the first Black union to sign a collective bargaining agreement with a major U.S. corporation. While Burton’s grandfather worked as a porter, her grandmother managed the household.

Even with higher pay and better union benefits, racially restrictive laws and policies kept Burton’s grandparents from owning a home. Restrictive covenants and residential ordinances, for example, limited where Black families could live. Banking structures systematically kept them from securing loans and investing, too.

These laws affected Black individuals and People of Color across the country until 1968 when they were deemed illegal (though you can still find remnants of these laws today, according to an investigative report by NPR.)

“My grandparents lived in the Black belt of the south side of Chicago,” Burton says, “off 47th street and Calumet, in an apartment they rented. My great aunts lived on 55th and Wabash and they rented, too. I always found it odd as a little girl that they didn’t own a house.”

As Burton learned more about the various prohibitions for Black Americans, she began to understand the long-term effect of being barred from buying homes in suburban communities and building equity.

Burton’s maternal grandfather died in 1957. Her grandmother lived decades longer, but “couldn’t build any wealth,” despite receiving her husband’s union pension, which without, would have left her destitute, says Burton. “She died in 1999 and never owned a home.”

Personal finance classes can chip away at racial wealth gaps

Decreasing racial wealth gaps will take time, but a key factor is ensuring communities of color have access to financial literacy classes. Having a basic understanding of our financial system, the effects of debt, and how to build wealth, would benefit all students, but especially students of color. However, only 27 states require schools to offer a course in personal finance, and only 18 require that all students take it to earn a diploma. In May, Indiana became the 18th state to add a personal finance course as part of its graduation requirement, beginning with the class of 2028.

A chief advantage of requiring a stand-alone class is that all students would have access to the content. In states that don’t require it, students of color and those from lower income families are less likely to learn about the topic at school, putting those students at a disadvantage for making informed financial decisions. It exacerbates the racial wealth gaps that have always existed in the U.S.

To help decrease these gaps, NEA supports the adoption of the National Standards for Personal Financial Education, created by the Jump$tart Coalition and the Council for Economic Education.

These standards provide educators with a “framework for a complete personal finance curriculum” for students from elementary through high school. Topics include earning income, spending, saving, investing, credit, and managing risk.

Plus, they address economic inequity including topics on race and gender wage gaps, discrimination in borrowing, and economic and employment experiences based on ethnicity and gender.

Understanding basic economics also prepares students to be voters with a savvy understanding of how leaders’ decisions affect their pocketbooks and the fate of public schools. Moreover, students care about money and want to learn more how to manage it.

“Students aren’t necessarily going to need calculus classes for their future, but everyone needs to know how to be a fiscally responsible human being,” Pam Brockmeyer, a Florida math teacher who includes the principles of personal finance in her math classes, told NEA Today last spring, “They want to know the difference between credit and debit, good or bad credit, and how using the cash advance stores they see could impact their finances.”

NEA resources

NEA provides personal finance resources including standards, lesson plans, teaching materials, and games, to help students gain the financial literacy skills they’ll need to manage their financial resources effectively throughout their lives.

Visit Tools for Teaching Financial Literacy and Resources for Teaching Financial Literacy to learn more.